I recently came across a concept in a law review article (yes, I read law review articles in my free time) that’s new to me: Citation Stickiness, by Kevin Bennardo & Alexa Z. Chew. From the abstract:

A citation is sticky if it appears in one of the parties’ briefs and then again in the court’s opinion. Imagine that the parties use their briefs to toss citations in the court’s direction. Some of those citations stick and appear in the opinion—these are the sticky citations. Some of those citations don’t stick and are unmentioned by the court—these are the unsticky ones. Finally, some sources were never mentioned by the parties yet appear in the court’s opinion. These authorities are endogenous—they spring from the internal workings of the court itself.

So a sticky citation is one that a court adopts/cites from a party’s brief. Seems straightforward enough. That’s the point of your brief – to provide a persuasive argument and precedent for your client. Lawyers should be trying to provide the most relevant cases to the court. But the authors found:

We analyzed 325 cases in the federal courts of appeals. Of the 7552 cases cited in those opinions, more than half were never mentioned in the parties’ briefs.1A few words on sample size. In all, our 325 judicial opinions contained 7552 unique case citations; the briefs filed in those 325 cases contained 23,479 unique case citations. When thinking about sample size, it is useful to think in terms of citations—7552 in the opinions and 23,479 in the briefs—rather than in terms of 325 cases.

Oh.

Citations in Briefs are Almost Never Cited

It would seem that lawyers aren’t doing a very good job of providing courts with relevant authorities. Instead, courts are having to do much of the heavy lifting themselves.

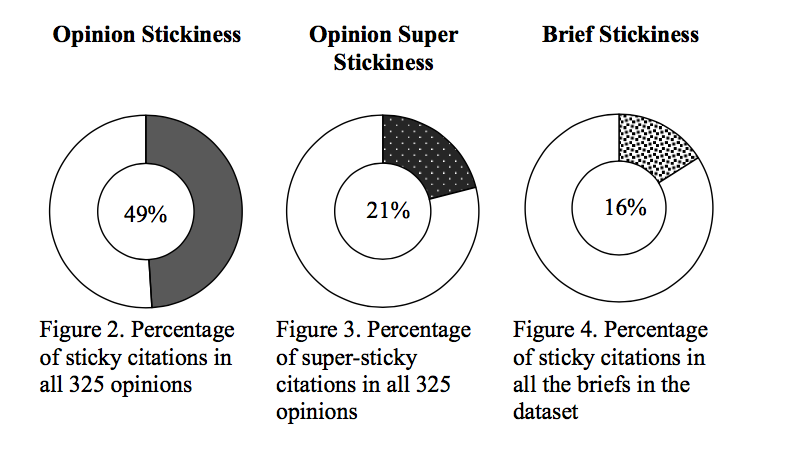

Using the nomenclature we invented, the overall stickiness percentage in our 325-opinion dataset was 49%. This means that 49% of the 7552 cases that were cited in the courts’ opinions had been cited by at least one party in a brief. The other 51% were endogenous—they originated from somewhere else, most likely the courts’ own research. Of all the cases cited in the 325 opinions, only 21% were cited by both parties in their briefs. To coin some more nomenclature, we’ll refer to case citations that appeared in both parties’ briefs and then again in the opinion as super sticky…

In our 325-case data set, the parties cited 23,479 cases. Of those, only 16% were later cited by the courts in their opinions—or to use our nomenclature, only 16% of the cases cited in the briefs were sticky. And of the 4276 cases cited by both parties in their briefs, only 38% were sticky (later cited by the courts in their opinions). In other words, if a party cited a case in a brief, there was only a 16% chance that the court would also cite that same case—and an 84% likelihood that the court would not mention the case (emphasis added).

I bet if you asked most lawyers if they thought that they were only getting around 16% of their cases cited in court’s opinions, they’d reject the notion. But the research proves otherwise.

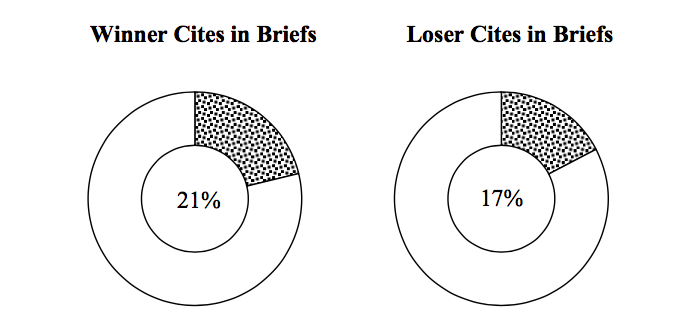

The vast majority of cases cited by lawyers in their briefs never show up in court opinions. And surprisingly, the difference in winning and losing briefs isn’t that great either.

An Opportunity in Citation Stickiness for Legal Research Platforms?

Given that lawyers are advocates for their clients, they’re likely citing case law that they believe is most persuasive to their position. Opposing counsel provides alternative arguments and citations in the best interest of their client. And the lawyers being paid to provide the best arguments and research for their clients. But the results speak for themselves – courts are providing over 50% of the cases cited in their opinions. A large amount of original legal research is being done when courts are drafting opinions.

The research is too new at the moment to draw too many conclusions, but hopefully more research will be done on this front. Practically speaking, it would be interesting to see some of the legal research companies make some steps in this direction. Most legal research platforms merely rank case law regarding how often it has been cited, clarified, or overruled (Shepardizing, KeyCite, etc). I think it would be great to see a “Stickiness rating” of a court opinion while doing research. While this study only found a small percentage difference in the number of referenced citations in winning and losing briefs – I don’t think any lawyer would not want a 4% higher chance of winning their case.

Read the entire paper below.

Bennardo, Kevin and Chew, Alexa, Citation Stickiness (April 19, 2019). 20 Journal of Appellate Practice & Process, Forthcoming. Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3375050

References