I’ve been pretty vocal lately that I think Facebook is bad, and should feel bad about itself. I took the app off my phone over a year ago. The amount of tracking that goes on through it is insane.

Great @WIRED piece on the internal machinations of Facebook. Takeaway: if you’re going to leak stuff – ALWAYS use a burner phone disconnected from ANY of your online accounts. https://t.co/GP64j3YFUb pic.twitter.com/Oge0s4Gx3w

— Keith Lee (@associatesmind) February 13, 2018

Anyway, I only use Facebook on a desktop now, and even then my use has declined to almost nothing. My social media use is limited almost exclusively to Insta, Twitter, & LawyerSmack.

But most people post all types of stuff on Facebook. It’s a treasure trove of information during litigation. But the difficulty often lies in determining what is discoverable and relevant to the matter at hand. This issue recently came up on appeal in New York.

Forman v. Henkin

This was a case that came from a riding injury. Plaintiff fell from a horse owned by defendant and suffered debilitating injuries that resulted in cognitive decline. As part of the Plaintiff’s proof, she claims she had an active lifestyle as documented on her Facebook account. But six month after the accident she deactivated her account due to depression and seclusion.

Plaintiff alleges that she was injured when she fell from a horse owned by defendant ,suffering spinal and traumatic brain injuries resulting in cognitive deficits, memory loss, difficulties with written and oral communication, and social isolation. At her deposition, plaintiff stated that she previously had a Facebook account on which she posted “a lot” of photographs showing her pre-accident active lifestyle but that she deactivated the account about six months after the accident and could not recall whether any post-accident photographs were posted. She maintained that she had become reclusive as a result of her injuries and also had difficulty using a computer and composing coherent messages. In that regard, plaintiff produced a document she wrote that contained misspelled words and faulty grammar in which she represented that she could no longer express herself the way she did before the accident. She contended, in particular, that a simple email could take hours to write because she had to go over written material several times to make sure it made sense.

Plaintiff won at the lower court. But on appeal:

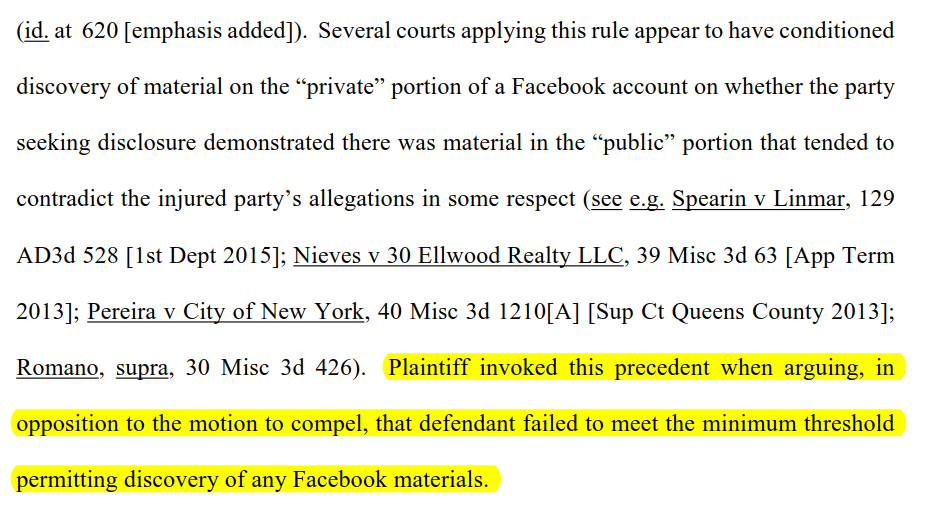

Discovery Requests That Are Appropriately Tailored And Reasonably Calculated Are Allowed

The Court goes on to lay out New York’s long standing discovery rules: as long as requests are appropriately tailored and reasonably calculated to yield relevant information they’re probably okay.

Before discovery has occurred – and unless the parties are already Facebook “friends” – the party seeking disclosure may view only the materials the account holder happens to have posted on the public portion of the account. Thus, a threshold rule requiring that party to “identify relevant information in [the] Facebook account” effectively permits disclosure only in limited circumstances, allowing the account holder to unilaterally obstruct disclosure merely by manipulating “privacy” settings or curating the materials on the public portion of the account. Under such an approach, disclosure turns on the extent to which some of the information sought is already accessible – and not, as it should, on whether it is “material and necessary to the prosecution or defense of an action” (see CPLR 3101[a]).

New York discovery rules do not condition a party’s receipt of disclosure on a showing that the items the party seeks actually exist; rather, the request need only be appropriately tailored and reasonably calculated to yield relevant information. Indeed, as the name suggests, the purpose of discovery is to determine if material relevant to a claim or defense exists. In many if not most instances, a party seeking disclosure will not be able to demonstrate that items it has not yet obtained contain material evidence. Thus, we reject the notion that the account holder’s so-called “privacy” settings govern the scope of disclosure of social media materials.

But this also doesn’t mean that you have carte blanche to dig through someone’s account. The Court suggests a two step process:

- Consider the accident, and surrounding facts, to determine if there is relevant information on Facebook.

- Balance the utility of discoverable evidence against the privacy concerns of the account holder, and then tailor an order that is specific to the situation

That being said, we agree with other courts that have rejected the notion that commencement of a personal injury action renders a party’s entire Facebook account automatically discoverable (see e.g. Kregg v Maldonado, 98 AD3d 1289, 1290 [4th Dept 2012] [rejecting motion to compel disclosure of all social media accounts involving injured party without prejudice to narrowly-tailored request seeking only relevant information]; Giacchetto, supra, 293 FRD 112, 115; Kennedy v Contract Pharmacal Corp., 2013 WL 1966219, *2 [ED NY 2013]). Directing disclosure of a party’s entire Facebook account is comparable to ordering discovery of every photograph or communication that party shared with any person on any topic prior to or since the incident giving rise to litigation – such an order would be likely to yield far more nonrelevant than relevant information. Even our broad disclosure paradigm, litigants are protected from “unnecessarily onerous application of the discovery statutes” (Kavanaugh, supra, 92 NY2d at 954).

Rather than applying a one-size-fits-all rule at either of these extremes, courts addressing disputes over the scope of social media discovery should employ our well-established rules – there is no need for a specialized or heightened factual predicate to avoid improper “fishing expeditions.” In the event that judicial intervention becomes necessary, courts should first consider the nature of the event giving rise to the litigation and the injuries claimed, as well as any other information specific to the case, to assess whether relevant material is likely to be found on the Facebook account. Second, balancing the potential utility of the information sought against any specific “privacy” or other concerns raised by the account holder, the court should issue an order tailored to the particular controversy that identifies the types of materials that must be disclosed while avoiding disclosure of nonrelevant materials.

In a personal injury case such as this it is appropriate to consider the nature of the underlying incident and the injuries claimed and to craft a rule for discovering information specific to each. Temporal limitations may also be appropriate – for example, the court should consider whether photographs or messages posted years before an accident are likely to be germane to the litigation. Moreover, to the extent the account may contain sensitive or embarrassing materials of marginal relevance, the account holder can seek protection from the court (see CPLR 3103[a]). Here, for example, Supreme Court exempted from disclosure any photographs of plaintiff depicting nudity or romantic encounters.

The court goes on to explain that whle privacy is important, private materials can also be relevant. Medical records (private, HIPPA-protected) often become relevant once a lawsuit is filed.

Plaintiff suggests that disclosure of social media materials necessarily constitutes an unjustified invasion of privacy. We assume for purposes of resolving the narrow issue before us that some materials on a Facebook account may fairly be characterized as private. But even private materials may be subject to discovery if they are relevant. For example, medical records enjoy protection in many contexts under the physician-patient privilege (see CPLR 4504). But when a party commences an action, affirmatively placing a mental or physical condition in issue, certain privacy interests relating to relevant medical records – including the physician-patient privilege – are waived (see Arons v Jutkowitz, 9 NY3d 393, 409 [2007]; Dillenbeck v Hess, 73 NY2d 278, 287 [1989]). For purposes of disclosure, the threshold inquiry is not whether the materials sought are private but whether they are reasonably calculated to contain relevant information.

Taking all of the above into account:

- The Court finds that discovery of material in the plaintiff’s Facebook account likely would lead to relevant information.

- The lower court had exercised its discretion in excluding nudity and romantic encounters.

- Due to the deactivation of the account it was naturally time limited.

- Facebook messages revealing the timing and number of characters in posted messages would be relevant to plaintiffs’ claim that she suffered cognitive injuries

Applying these principles here, the Appellate Division erred in modifying Supreme Court’s order to further restrict disclosure of plaintiff’s Facebook account, limiting discovery to only those photographs plaintiff intended to introduce at trial. With respect to the items Supreme Court ordered to be disclosed (the only portion of the discovery request we may consider), defendant more than met his threshold burden of showing that plaintiff’s Facebook account was reasonably likely to yield relevant evidence. At her deposition, plaintiff indicated that, during the period prior to the accident, she posted “a lot” of photographs showing her active lifestyle. Likewise, given plaintiff’s acknowledged tendency to post photographs representative of her activities on Facebook, there was a basis to infer that photographs she posted after the accident might be reflective of her post-accident activities and/or limitations. The request for these photographs was reasonably calculated to yield evidence relevant to plaintiff’s assertion that she could no longer engage in the activities she enjoyed before the accident and that she had become reclusive. It happens in this case that the order was naturally limited in temporal scope because plaintiff deactivated her Facebook account six months after the accident and Supreme Court further exercised its discretion to exclude photographs showing nudity or romantic encounters, if any, presumably to avoid undue embarrassment or invasion of privacy.

In addition, it was reasonably likely that the data revealing the timing and number of characters in posted messages would be relevant to plaintiffs’ claim that she suffered cognitive injuries that caused her to have difficulty writing and using the computer, particularly her claim that she is painstakingly slow in crafting messages. Because Supreme Court provided defendant no access to the content of any messages on the Facebook account (an aspect of the order we cannot review given defendant’s failure to appeal to the Appellate Division), we have no occasion to further address whether defendant made a showing sufficient to obtain disclosure of such content and, if so, how the order could have been tailored, in light of the facts and circumstances of this case, to avoid discovery of nonrelevant materials.

In sum, the Appellate Division erred in concluding that defendant had not met his threshold burden of showing that the materials from plaintiff’s Facebook account that were ordered to be disclosed pursuant to Supreme Court’s order were reasonably calculated to contain evidence “material and necessary” to the litigation. A remittal is not necessary here because, in opposition to the motion, plaintiff neither made a claim of statutory privilege, nor offered any other specific reason – beyond the general assertion that defendant did not meet his threshold burden – why any of those materials should be shielded from disclosure.

Accordingly, the Appellate Division order insofar as appealed from should be reversed, with costs, the Supreme Court order reinstated and the certified question answered in the negative.

You can read the full opinion here.

For more on social media discovery: