A few years ago, a couple of law professors surveyed practicing lawyers and judges on the quality of legal writing from new lawyers. The results?

More than 93% of the responding practicing attorneys and judges believed that the briefs and memoranda they saw were “marred by basic writing problems,” including a lack of focus (76.1%), failure to develop an overall theme or theory of the case (71.4%), and failure to be persuasive (66.4%). 1Susan Hanley Kosse & David T. Butleritchie, How Judges, Practitioners, and Legal Writing Teachers Assess the Writing Skills of New Law Graduates: A Comparative Study, 53 J. LEGAL EDUC. 80, 85 (2003).

That’s to say: most brief writing by new lawyers is awful. And this isn’t 1Ls we’re talking about, but practicing lawyers. Most lawyers can’t write for squat. Which is unfortunate because writing is thinking. If you don’t write well, it’s likely you don’t think well. Which is a problem, because that’s essentially what clients hire you for.

Contents

How To Write a Legal Brief

Despite that you should have learned all this in Legal Research & Writing back in law school, here is a brief introduction (or refresher) on brief writing. Follow the below steps and you’ll draft better briefs.

Organize and outline your arguments

Judges are busy. They have voluminous amounts of documents to review at any given time. Often they will go weeks, if not months, between touching the same case twice. Any brief you put before a judge needs to:

- Be well organized

- Provide a roadmap for the judge to follow

- Prioritize strong arguments first

Develop a theme for your brief

You (hopefully) learned about this concept in law school. Many people refer to it as the “theory/theme of the case.” Shotgunning a dozen different ideas at a judge is a surefire way for them to forget all of them.

Again, conceptualize your reader: a busy, overworked judge (and clerks) who has a hundred other briefs to look at after yours. They do not have the time for deep contemplation of your brief. You need a central theme which suffuses every part of your brief.

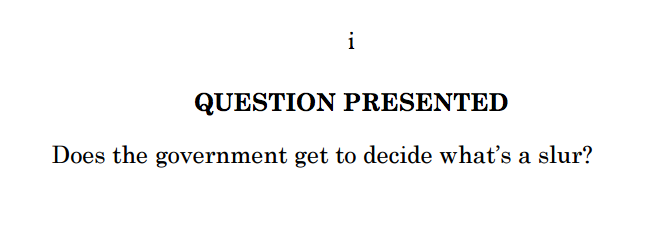

For an excellent example, see the amicus curiae brief (PDF) filed by the Cato Institute in Lee v. Tam. Just look at the question presented:

Simple, to-the-point, and incredibly evocative. The question effectively frames the matter presented before the Court in such a fashion as to be persuasive even before the brief has been read. The brief consistently reinforces the message that arose from the question presented.

Use CRAC to analyze legal issues

Let’s not re-invent the wheel here. This isn’t the time for you to indulge in creative writing. Follow what works. Almost everyone is taught the CRAC method of legal analysis in law school. CRAC: Conclusion -> Rule -> Application ->Conclusion. Use it.

- Conclusion. What is the conclusion you want to judge to make after reading your brief.

- Rule. What is the law that supports your conclusion.

- Application. Explain how the law applies to the issues.

- Conclusion. Restate the conclusion to the judge.

Use structural writing techniques to help guide the reader

Structural writing techniques are the basic building blocks of organizational writing that often get short shrift from lawyers. Or lawyers use them, but are completely awful at it.

Effective Headings

Headings help give the reader an idea of what is going to be addressed in a particular section.

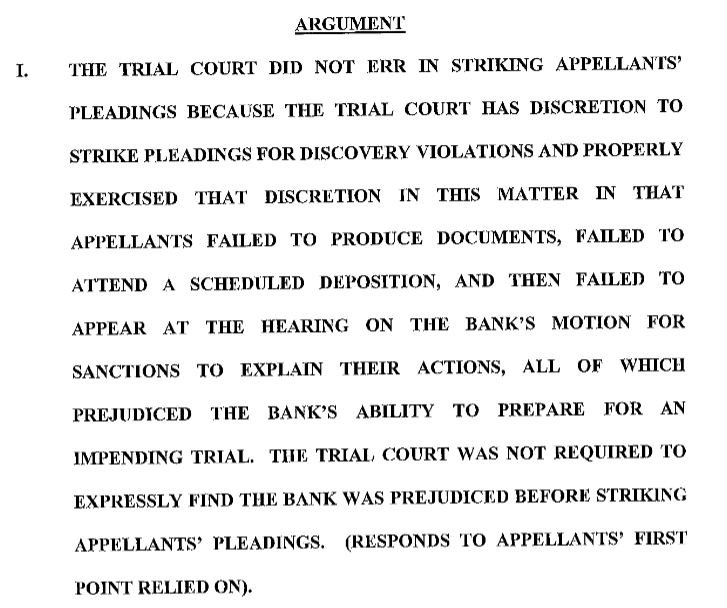

Bad example:

That heading is absolute garbage. You didn’t even bother reading after a couple of lines. Your eyes just glazed over. You think a judge is going to be different? LOL.

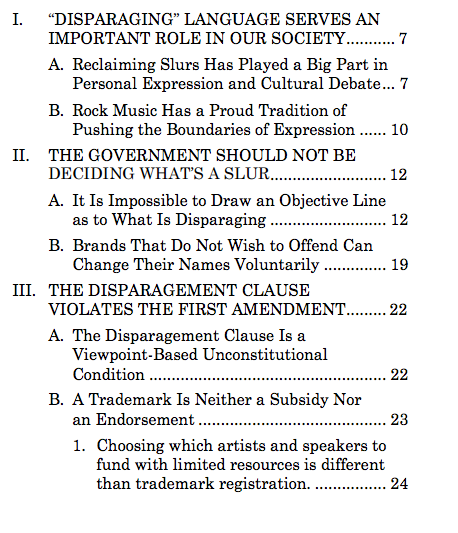

Let’s go back to the Lee v. Tam brief:

Headings are signposts that let the reader know where you are taking them. Not journeys unto themselves.

Table of contents

A good table of contents (see above) lays out the briefs logical structure. It also helps the judge easily find and reference material from your brief. A table of contents might not be applicable in shorter briefs, but they are necessary in longer ones.

Summaries

Dense, technical, legal writing can be exhausting to read. Summaries help provide background, frame issues, or highlight important facts or evidence. Again, go back to the Lee v. Tam brief. It’s 50 pages long, but they have an excellent summary of the case on pages 1 to 5. But summaries aren’t just for appellate briefs.

- Going to pull a large blockquote? Judge probably won’t read it. Summarize the blockquote before or after in one to two sentences.

- Going to write a long dense paragraph? If you can’t break it apart for some reason, make sure you have a topic sentence.

- Remember that section above about headings? Headings are, yep, summaries.

Address threshold issues before diving into the details of the case

Before you start in on the merits of the case, make sure you have addressed any and all threshold issues: personal and subject matter jurisdiction, proper venue, statute of limitations, etc. The purpose for this is twofold:

- It lets the court know that the case before it is ready to be adjudicated.

- You have to do your due diligence. You know your case doesn’t have a fatal procedural/technical flaw before you begin to get to the merits.

Effective brief writing is an essential skill for new lawyers

The majority of advocacy undertaken by lawyers is written advocacy. You’ll spend far more time drafting legal documents than you ever will in a courtroom. Dedicating yourself to consistently improving your writing skills should be one of the fundamental aspects of your professional development.

Remember, your professional development is your responsibility, no one else’s. Get to it.

If you want more writing help, I encourage you to download the below:

References