“Everything we hear is an opinion, not a fact. Everything we see is a perspective, not the truth.”

― Marcus Aurelius, Meditations

Being an effective negotiator is an incredibly important aspect of being a lawyer. Whether it be a contract dispute or a bitter custody battle, negotiation comes to play on a regular basis in the representation of clients.

Negotiation is not always a contested battle of wills. A couple who has fallen out of love, but still remain close friends, may want to negotiate a simple and easy divorce agreement. Two businesses locked in a dispute over a seven-figure fulfillment contract may want to battle to the last dime.

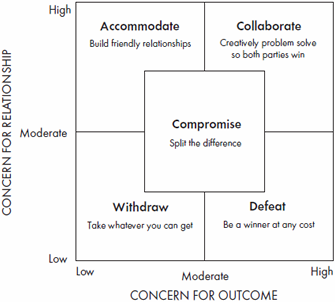

Generally speaking, negotiation styles fall into five-area model, ranked on two axis: concern for the value of continuing the relationship between the parties and concern for the outcome of the negotiation. The model is generally displayed as such:

If a negotiation falls in the upper quadrants of the model, it is unlikely that either side will engage in deceptive negotiating tactics. But when negotiations fall into the lower quadrants parties will do what they must in order to win.

That’s Just Called Being a Lawyer

In 1997, Kathleen M. O’Connor and Peter J. Carnevale published a paper in the Personality & Social Psychology Bulletin, entitled Negotiation Strategy: Misrepresentation of a Common-Value Issue:

Conflicts sometimes involve issues for which both parties want the same outcome, although frequently parties fail to recognize their shared interests. These common-value issues set the stage for a nasty misrepresentation strategy: feigning opposed interest on the common-value issue to gain an advantage on other issues.

They go on to use a hypothetical to point out the use of misrepresentation in a real world setting:

A husband and wife enter divorce negotiations. Two issues are on the table: custody of the children and the level of alimony payments to the wife. She wants custody of the children and a generous alimony payment. And she assumes that her husband wants custody of the children, too, and to provide only a paltry alimony payment. But the fact is that he actually does not want custody of the children.

In other words, both the husband and the wife want the same thing on this issue–for the children to go with her. But the husband feigns opposed interest on the custody issue and thus gains an advantage. He states to her: “Ok, take the children, but in exchange you will have to accept the smaller alimony.” She agrees, thinking that they each achieved something on the two issues. But, in fact, the husband, via misrepresentation, achieved his preferred position on both issues.

Misrepresentation of common value in negotiation is, indeed, nasty. But it is often effective, at least as far as producing favorable outcomes for the user.

For ivory tower psychology researchers this is “nasty” behavior. Yet any experienced lawyer reading this is laughing and shaking their head.

“Wait. A party in negotiation might not be completely 100% up-front and true regarding the motivations behind their position?!?”

The No-Man’s Land of Ethics

In a paper on the ethics of misrepresentation by omission, Barry Temkin wrote on ethical constraints on a lawyer’s misleading statements and omissions:

Settlement negotiations are, in many respects, the ethical no-man’s land of legal practice. Settlement negotiations are frequently conducted in the absence of judicial supervision and without clear parameters or guidelines in the Model Rules or ABA Model Code of Professional Responsibility (“Model Code”). Lawyers posture, threaten, bluff, wheedle, obscure, misdirect, and, often, outright mislead adversaries in order to obtain advantage for their clients. Scholars of negotiation have widely recognized the “not-so-subtle art of misdirection,” which can include evasiveness, silence, or a “true but incomplete statement of facts.”

In an increasingly competitive legal market, and in the perceived absence of judicial oversight or repercussions for hardball tactics, lawyers frequently push the envelope in an effort to impress or gain advantage for clients. A lawyer who deliberately misstates a client’s settlement goals and bottom line is engaged in “puffing” which, most legal ethicists agree, “would often be considered permissible.”

Yet that is not to say negotiation is a free-for-all, ethics-free paradise. It is one thing to engage in “puffery,” another to engage in complete misrepresentation to the opposing party. Yet lawyers are often torn between their duty to their clients and the duty to avoid misrepresentations to others.

Presenting a low ball offer to feel the other party out is common practice, and a part of negotiating whether it is a multi-million dollar deal or buying a car. But that does not mean that a lawyer can blatantly lie or create spurious facts to support their position in the interest of zealously representing a client.

Instead a lawyer must be guided by their own moral compass. As Temkin notes “Reconciling the duty of zealous advocacy with the highest standards of honesty and fair dealing is one of the most difficult tasks facing attorneys.” That means a lawyer must have a strong sense of what is truthful and just.

Lawyers must recognize that the Model Rules and Ethical Standards are not a high bar to be reached, but a starting point from which to move forwards.

For further reading on ethics in negotiation, see:

- ABA’s Ethical Guidelines For Settlement Negotiations

- Misrepresentation by Omission in Settlement Negotiations: Should There Be A Silent Safe Harbor?

- Negotiation Ethics: How to Be Deceptive without Being Dishonest/How to Be Assertive without Being Offensive

- The Ethics of Negotiation: Are There Any?

- Attorney Negotiation Ethics: An Empirical Assessment

[divider]

I talk about ethics much more in my book, but it might give you the sadz.