If you’ve been out of the loop the past few years, crowdfunding has become a major force in how capital is raised – outside of vcs, angels, banks, and the like. Crowdfunding is the process by which business, causes, and people raise monetary contributions from a large number of people, typically via the internet. It allows anyone with an idea or project to bypass the traditional financial apparatus of funding.

Like many things that seem new and amazing on the internet, it’s actually not a new idea. Perhaps the most iconic and lasting example of crowdfunding is the Statue of Liberty. Financing for it had crumbled in the 1880s and it wasn’t until publisher “Joseph Pulitzer of the New York World started a drive for donations to complete the project that attracted more than 120,000 contributors, most of whom gave less than a dollar,” was Lady Liberty able to be finished. Yet the idea never really took hold in the 20th century.

But given the internet’s ability to instantly reach anyone/anywhere, along with the ability to instantly transfer capital, crowdfunding has taken off with a with unexpected force. Individual donations/funding might be small, but cumulatively they add up to a lot of dough:

After collecting data on 1,250 active crowdfunding platforms (CFPs) worldwide and undertaking significant further research, the results reveal that CFPs raised $16.2 billion in 2014, a 167% increase over the $6.1 billion raised in 2013.

In other words, crowdfunding is skyrocketing. Just as it’s almost impossible to walk into a Starbuck’s in Silicon Valley without running into a “founder,” you’re just as likely to run into a “funder” at a McDonald’s these days.

Crowdfunding Flavors

There are two primary types of crowdfunding that draw the most money and attention, Rewards Crowdfunding & Equity Crowdfunding:

- Rewards Crowdfunding: entrepreneurs pre-sell a product or service to launch a business concept without incurring debt or sacrificing equity/shares.

- Equity Crowdfunding: the backer receives shares of a company, usually in its early stages, in exchange for the money pledged.

Along with the above two, there is also litigation crowdfunding (really litigation financing) which I’m sure many lawyers are already familiar with. This past week the New York Times examined this trend, asking whether or not it’s compromising the legal system. While this type of crowdfunding still tends to primarily attract educated, institutional investors, companies like LexShares are seeking to allow a wider range of investors to put their money into lawsuits.

Finally, there is also charitable crowdfunding. Again, this isn’t exactly new, it’s how charities have always functioned. But many charities have been helped by the buzz around crowdfunding and have latched onto it to drive donations.

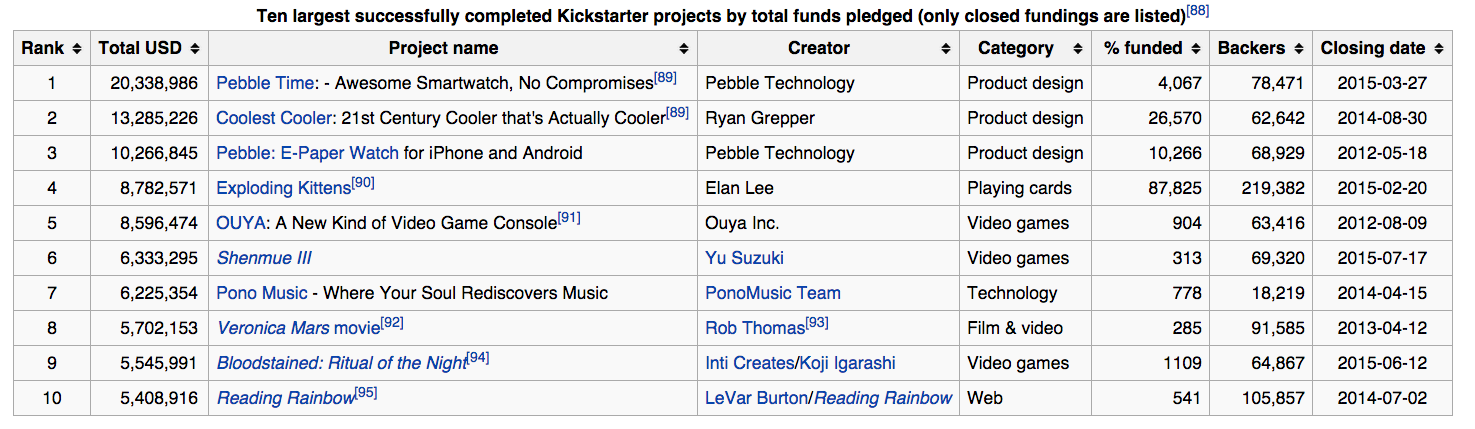

Beyond the types of crowdfunding that exist is the variety of CFPs available. The most notable and high profile is Kickstarter, started in 2009 (though it has now been eclipsed). Developed as a platform to enable people to back a variety of projects, Kickstarter really took off once it was adopted by game companies. Many of the most successful projects on the site have been games or in game-related media.

Yet Kickstarter has been surpassed by the rise of GoFundMe, which allows people to raise money for events ranging from life events such as celebrations and graduations to challenging circumstances like accidents and illnesses. The focus is not on business projects, but on helping people through events in their personal lives.

The largest global CFP is IndieGoGo, launched in 2008. While launching before Kickstarter, and raising large amounts of money, it hasn’t quite caught on in the same way as Kickstarter. Of note, Indiegogo is generally considered more tolerant of projects and has looser guidelines than Kickstarter.

Other notable CFPs include Crowdrise (uses gamification and a rewards point system to engage users), Patreon (must pledge an on-going amount, creative projects only), EquityNet (focused on investors and obtaining equity in companies, not “rewards”), and newcomers like ReCurrency (though they had a rough start).

All together, these CFPs have enabled thousands of businesses and people around the world to pursue their ideas. Start a company, write a book, design jewelry. They’ve helped people pay for cancer treatment, recover from car accidents, and celebrate bar mitzvahs. At the same time, they’ve allowed funders to help out other people and perhaps feel a bit of pride in contributing to someone else’s hopes and dreams, while often receiving rewards, bonuses, or even equity for doing so. As a whole, CFPs are likely a net gain for society.

But like most good things, CFPs also have the potential to be abused.

Consumer Protection And Private Class Actions

A few years ago the Federal Trade Commision (FTC) took a look around at all this money moving around outside the traditional financial system and said: “wait a minute.” The established separate task forces to track emerging trends in financing and have been issuing reports on the industry for some time. And earlier this year, for the first time ever, the FTC initiated proceedings against a crowdfunded project, resulting in a $111,793.71 judgment:

The Federal Trade Commission has taken legal action against the deceptive tactics of a project creator who raised money from consumers to produce a board game through a Kickstarter campaign, but instead used most of the funds on himself. The defendant has agreed to a settlement that prohibits him from deceptive representations related to any crowdfunding campaigns (PDF of proposed Order) in the future and requires him to honor any stated refund policy.

Also for the first time at the state level, earlier this year Washington announced the successful conclusion of the first enforcement action in the nation against a crowdfunded project that didn’t follow through on its promise to backers:

King County Superior Court Commissioner Henry Judson ordered Edward J. Polchlopek III, otherwise known as Ed Nash, and his company, Altius Management, to pay $54,851 as a result of the 2012 “Asylum Playing Cards” Kickstarter campaign.

The court ordered a total of $668 in restitution for the 31 Washington state backers, $31,000 in civil penalties for violating the state Consumer Protection Act ($1,000 per violation), and $23,183 to cover the costs and fees involved in bringing the case…

The AGO filed this lawsuit on behalf of Washington state consumers under the state Consumer Protection Act. Affected consumers from other states are encouraged to file a complaint with their state attorney general to seek restitution.

These two instances likely set the stage for a wave of actions against businesses and people who run successful crowdfunding campaigns and then don’t on the projects. While these two instances have been brought by the FTC and a state AGO, going forwards expect their to be private class actions brought by the plaintiff’s bar, especially in the wake of the recent Alabama case, Lisk v. Lumber One Wood Preserving LLC (PDF of opinion), No. 14-11714, — F.3d —, 2015 WL 4139740. The Court held that state consumer fraud class actions may proceed in federal court even if the state consumer fraud statute expressly forbids class actions. If other courts follow suit, plaintiffs in at least eight other states that currently prohibit consumer fraud class actions (Georgia, Iowa, Louisiana, Mississippi, Montana, South Carolina, Tennessee, and Virginia) can circumvent these prohibitions simply by filing in federal court.

Worth noting, any coming lawsuits will likely focus exclusively on seeking recompense from the project creators themselves, not the CFPs which should retain immunity under 47 U.S. Code § 230 (see Home Decor Ctr., Inc. v. Google, Inc. (PDF of ruling), 2013 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 185298, (C.D. Cal. May 9, 2013) fact that a website operates a commercial business or makes a profit has no relevance to the immunity determination).

Too Much Of A Good Thing

Given the wide range of CFPs, the number of projects on offer, and the amount of money involved, it is only given that there will be a continued rise in crowdfunding campaigns that reach their goals, but never deliver. With the state and Federal government’s having shown that consumers have a green light to go after crowdfunded projects, expect more to be coming down the pipe.

Crowdfunding was a nice happy place of rainbows and ponies while it lasted. Here come the lawyers.

[divider]

Resources:

- A Brief History of Crowdfunding, © 2014-2015 Freedman and Nutting (PDF)

- Crowdfunding: Transforming Customers Into Investors Through Innovative Service Platforms, Andrea Ordanini,Lucia Miceli,Marta Pizzetti, A. Parasuraman (PDF)

- The Crowdfunding Centre Reports