In the long period since my last post, I’ve thought a lot about the applicability of recounting these battles to you all. I first entitled this series “…Battle/Debate Strategy” because I thought the “Debate” part would appeal to you lawyer-types. But the truth is that a working knowledge of these crucial historical moments informs the knower and equips him/her for a much broader spectrum of challenges than debate. In my life, when I encounter a problem that I don’t know how to approach (much less solve), appealing to the small bit of wisdom gained from these tales is valuable. At the very least, it gives me perspective and a starting point from which to engage the challenge. With that, we’ll continue with the series, focusing on a little-known battle that changed the face of the earth, literally.

Alexander Sets His Eyes on Tyre

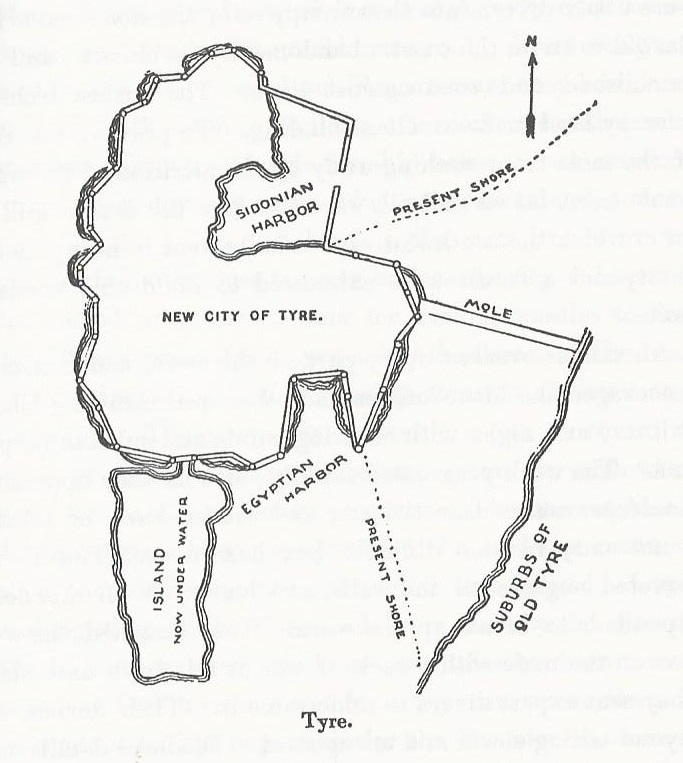

By 332 BC, Alexander had subdued Asia Minor (modern Turkey) and continued down the coast (through modern Syria and Lebanon) with the aim of conquering the Persian Empire. His next major objective was Egypt, but to venture to that ancient land without subduing the Persian-controlled southeast Mediterranean ports would severely endanger his supply network and, thereby, threaten his entire campaign. So, as he approached the island-fortress of Tyre, he knew that the subjugation of that proud city was critical. Although within the Persian sphere of hegemony, Tyre was an unconquered city populated (as it always had been) by Phoenicians. The fortified Old Town was on the mainland, but the near-impenetrable New Town was half a mile out to sea. In the 6th century BC, as the Persian military and political influence inexorably spread through the ancient Middle East, Tyre allied itself with Persia and was thus brought into the fold. More than simply a vassal state, though, Tyre was a prestigious center of Phoenician culture–and power. The Phoenicians constituted the largest and most effective portion of the Persian navy, the force that dominated the Sea. Until this point, the land-based army and supply routes of the Macedonians had allowed Alexander to avoid naval engagement, but to leave Tyre in his rear and march on to Egypt would be inconceivable.

Murum Aries Attigit

As with many of the cities he approached, Alexander offered a peaceful transition of power. He offered to spare the city and its inhabitants from violence if they would open the gates of the New Town to him and allow him to sacrifice to Herakles (Hercules) in their sacred temple. Unlike most of the cities he approached, Tyre refused. Never before had a foreign power (Persia included) been admitted into the island city, and they would not change the trend for a Macedonian. They had good reason to trust in their walls’ defenses should Alexander attack. Nebuchadnezzar II‘s thirteen year siege (586-573 BC) failed to subjugate the Old Town, and the new fortress was vastly more heavily fortified. So Alexander was left, navyless, to attempt to vanquish an unconquered island a kilometer distant from shore. With typical impetuosity, Alexander decided on a swift course of action. He would build a mole or causeway from the shore to the island and attack it directly; he had no time or patience for a prolonged siege and no means by which to enforce one.

from TA Dodge’s Alexander.

Therefore, beginning in the shallow waters near the coast, his engineers and laborers drove countless beams of cedar (cut from nearby forests) into the sea bed. Stones pillaged from the abandoned Old Town, earth, and wood were packed between the beams to form a two-hundred-foot-wide land bridge which soon extended toward the fortress. But as the sea floor became deeper near the island, construction became more difficult and slowed. Meanwhile, Alexander’s army had constructed great siege engines (mobile towers serving as armored platforms for archers and state-of-the art, torsion-powered artillery) and moved them to the end of the bridge to protect the ongoing construction and to begin the assault on the walls. The Tyrians, safely tucked away, counterattacked with their navy. The Macedonians fought off Tyrian vessels with catapulted stones and the like. But Tyrians’ achieved a great victory by means of a virtually unmanned transport ship, filled with combustibles, which was ignited and rammed into the causeway. Although the engines were covered with fire-retardant materials, the blaze engulfed and destroyed them. The fire severely compromised the integrity of the bridge, which was shortly washed away. The Macedonian army was forced to retreat to land, and Alexander’s plans and the effort of months were in ruins.

Defeat Is Not An Option

But we may learn, reader, from Alexander, who adapted. Until this moment, he had never possessed (much less commanded) a navy, but he saw that things must change. In the next weeks, he pieced together a fleet of over 200 ships from recently conquered states as well as from those seeking alliance. Thus reinforced and reinvigorated, he renewed the attack. His engineers began work on a larger causeway, this time built into the prevailing tides rather than across them. Siege engines were reconstructed; more catapults were set atop them. Alexander’s new fleet was now larger than that at the disposal of the Tyrians, and with it he blockaded their harbors.

For weeks, Tyre deployed a countermeasure for every stratagem Alexander used against them. Alexander wanted to undermine the walls; the Tyrians dropped loose boulders at their bases to prevent it. Alexander’s ships employed dredge mechanisms to remove them. The Tyrians sent mailed ships armed with scythes to cleave the dredges from their parent ships. Alexander advanced his own vessels, clad in mail, before the dredges to protect them and exchanged the tethering ropes for chains. Tyre sent divers to dispose of both from beneath the waves. Meanwhile, the land bridge grew. Exploiting a mid-day lull, the Tyrian fleet broke out of their blockaded northern (Sidonian) harbor, attacked, and greatly damaged the portion of Alexander’s fleet which was moored north of the causeway. He, who was at the moment with the southern fleet, circuited the island and took the Tyrian fleet from behind, routing it. With this final defeat of the Tyrian navy, Alexander was free to assault the walls with men, engines, and ship-borne battering rams.

After days of testing various points of defense, and after matching wits and ingenuity with the increasingly desperate Tyrians defending the walls, Alexander’s machines succeeded in creating a breach which would shortly be exploited to enter the city. In typical fashion (which would, eight years in the future, earn Alexander an arrow through the lung), he was among the first men to mount the wall and took several defensive towers. His forces advanced to the citadel, laying waste to what and whom they encountered along the way. Alexander pardoned the Tyrians who fled to and sheltered in the temple of Herakles. The other men (more than thirty thousand) were killed or sold into slavery.* Having sacrificed at the the temple as originally desired, Alexander staged games and gymnastic sports as a celebration. Tyre was retained as a naval station, but otherwise utterly destroyed. Yet the land bridge remained.

The falling walls of Tyre must have reverberated like a thunderclap in the fearful imaginations of the inhabitants of the western Persian Empire. The next major city, Jerusalem, surrendered without a fight. In fact, the Macedonians marched, without great conflict, into Egypt which opened its arms to Alexander, declaring him son of Amun (Zeus).

Alexander’s influences on posterity take many forms–political, cultural, martial, intellectual, and, in this case, geographic. His Tyrian causeway, “altered the flowing tides in such a manner that the ancient harbors have been filled up with deposits of mud, and the island has become a peninsula, nature’s monument to the almost superhuman labors of this greatest of captains.**”

[divider]

*Thousands of women, children, and elderly male citizens survived. They had been previously evacuated to Carthage.

** This sequence is described more eloquently and in greater detail in Theodore Ayrault Dodge’s Alexander, a masterful work which I have used for reference for this article. DaCapo Press of Cambridge, MA has republished the 1890 edition.