Today the Supreme Court handed down a significant decision in U.S. v. Windsor, striking down the Defense of Marriage Act (DOMA). Besides the decision, what was of particular interest to me was the reasoning behind the decision – unconstitutional animus. I would have never heard of the concept before (I didn’t really pay attention in Con law) except that I started reading about it in the work of Susannah Pollvogt in her article Unconstitutional Animus. Instead of trying to boil down a 50-page article on my own, I asked Professor Pollvogt if she wouldn’t mind explaining the doctrine in small words so I would understand it.

The following is her explanation of unconstitutional animus in the context of today’s decision.

U.S. v. Windsor

The first basis for Justice Kennedy’s decision striking down the federal DOMA was that the law interfered with the traditional power of the states to decide who may and may not get married. This reasoning has implications for the scope of federal power only.

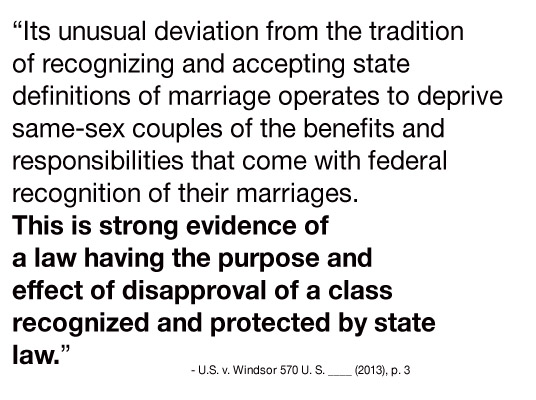

But the second basis cited in the decision—that DOMA was unconstitutional because it was based in unconstitutional animus—has profound implications for the future of marriage equality litigation throughout the country.

The doctrine of unconstitutional animus has lain dormant on the Supreme Court level since Justice Kennedy’s 1996 decision in Romer v. Evans. There, the Court held that Colorado’s Amendment 2 violated the Equal Protection Clause because it served no legitimate purpose other than to express hostility toward gays, lesbians, and bisexuals. In a bizarre decision with many “missing passages,” the Court concluded that animus was present because the law could not be explained any other way. Thus, the Romer decision provides little positive guidance for sussing out the presence of animus.

Three Other Animus Decisions

More helpful are the Court’s three other animus decisions. In 1973, there was Moreno v. Department of Agriculture. In that case, Congress sought to exclude “hippies” form receiving federal food stamp benefits, and so amended the Food Stamp Act to accomplish that result. In the course of debating the law, members of Congress declared openly the legislative record that their goal was to exclude a disfavored social group—“hippies” and “hippy communes”—from these benefits. The Court held that private biases such as there could not provide a basis for the public laws, and struck down the amendment on that basis.

In 1984, the Curt reached a similar conclusion with respect to private biases regarding interracial couples. At issue in Palmore v. Sidotti was a family court’s decision to remove a child from the custody of its mother because the mother, white, had remarried a black man. The family court determined that growing up in an interracial household would be detrimental to the child. The Supreme Court did not disagree that the child might face hardships due to the circumstances, but that by reacting to these private biases in its custody decision, the family court was essentially enshrining those beliefs in the law itself. This was impermissible.

The last animus case prior to Romer was City of Cleburne v. Cleburne Living Center. There, the city council denied a group-housing permit to a living center that wished to establish a group home for persons with cognitive disabilities. As part of their consideration of the issue, the city council heard opinion from neighbors of the proposed living center indicating that they were fearful of and prejudiced toward the would-be residents of the home. Consistent with Moreno and Palmore, the Court held the city government could not make a decision informed by such biases.

So What Counts As Evidence Of Animus?

After these cases, and Romer, and now Windsor, it is clear that animus (defined as hostility, animosity, prejudice, private bias, and/or fear) is not a valid basis for the public law. What is not clear is what exactly counts as evidence of animus.

For example, Moreno and Windsor represent the easy cases. In both instances, the legislative history behind the law explicitly stated that hostility toward a particular social group was the motivating force. Other laws that are based on such clear, impermissible grounds will fall as well.

We know that the district court in the Proposition 8 case also discerned the presence of animus based on the campaign literature surrounding the enactment of that law. But the Court did not reach the merits of Proposition 8, and so has yet to provide guidance on whether that type of evidence will suffice to reveal a law as constitutionally unsound.

Going forward, advocates of marriage equality should pay close attention to the Court’s animus jurisprudence, and assemble evidence that the marriage bans in their respective jurisdictions are similarly based on bare moral disapproval of same-sex couples.

Susannah Pollvogt blogs about her scholarship at Pollvogtarian, is a co-founder of SucceedLaw, and is a Visiting Lecturer at DU Law.

Susannah Pollvogt blogs about her scholarship at Pollvogtarian, is a co-founder of SucceedLaw, and is a Visiting Lecturer at DU Law.