In light of the Sequester, generously brought to us by our public servants, I have been considering the personality and traits of our leaders. To be sure, the contrarian tactics of the Republicans (I’m looking at you, Tea Party), have made political compromise and deal-making closer to a thing of myth than of reality. But I have been reflecting on the President’s role, in particular. Mr. Obama seems to me to be a well-intentioned, contemplative, intellectual politician. What he is not, as far as I can see, is a true leader. He doesn’t seem to have the charisma or persuasive abilities to bring divergent opinions or personalities into the fold, and his personality does not carry the weight to inspire or to move anyone to action. I don’t consider this deficiency to be a slight on the man, whom I generally like and whose other traits I admire. Indeed that critical spark which he lacks is a rare and cherished trait, and it is a lucky man (or woman) who possesses it.

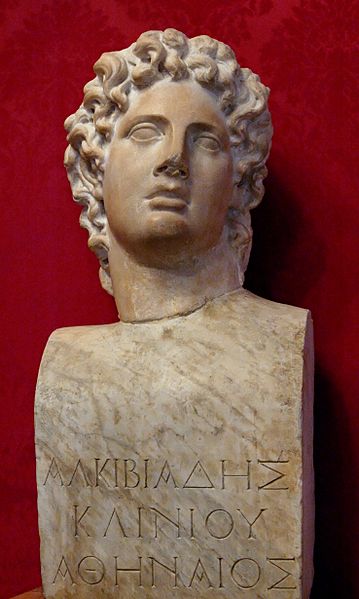

Considering the topic of charismatic figures of the past, one can think of many. But I have a favorite: Alcibiades, son of Cleinias. Imagine, at one moment in history, the most ambitious man, the most cunning man, the most charismatic man, the most handsome man, the greatest orator, the richest man, the most powerful man, a man with a first rate intellectual mind, all coinciding in a single person. Such was his influence that victory and glory followed him at every turn as he shifted alliances in the latter stages of the triangular Peloponnesian War. But more than acclaim followed him–intrigue and the envy, enmity, and hatred of his contemporaries (much of which was well-deserved) were also his traveling companions. Such was the curse of the most interesting historical figure I know.

Early Life

Alcibiades was born,1 in 450 BC in Athens into a powerful and ancient family, and, after the death of his father (in battle, at Coronea), he was raised and taught under the roof of Pericles, the most powerful Athenian of his generation. Most sources place young Alcibiades under the tutelage of Socrates, the great philosopher, and one of Plato’s Dialogues accordingly is named for him. In fact, Alcibiades literally owed Socrates his life, as the philosopher saved him from death in the Battle of Potidea in 432 BC.2 Only a few years later, Pericles succumbed to an outbreak of plague in Athens, and the young and rambunctious Alcibiades emerged as one of the premier politicians. As he vied for influence and followers with “colleagues” at the top levels of Athenian politics, the elder statesman, Nicias, with his more passive, cautious, and contemplative manner, emerged as his foil. This passage relates political maneuvering worthy of Odysseus or Themistocles:

Alcibiades first rose to prominence when he began advocating aggressive Athenian action after the signing of the Peace of Nicias. That treaty, an uneasy truce between Sparta and Athens signed midway through the Peloponnesian War, came at the end of seven years of fighting during which neither side had gained a decisive advantage…[Thucydides reports] that Alcibiades was offended that the Spartans had negotiated that treaty through Nicias and Laches, overlooking him on account of his youth.

Disputes over the interpretation of the treaty led the Spartans to dispatch ambassadors to Athens with full powers to arrange all unsettled matters. The Athenians initially received these ambassadors well, but Alcibiades met with them in secret before they were to speak to the [Athenian Assembly] and told them that the Assembly was haughty and had great ambitions. He urged them to renounce their diplomatic authority to represent Sparta, and instead allow him to assist them through his influence in Athenian politics. The representatives agreed and, impressed with Alcibiades, they alienated themselves from Nicias, who genuinely wanted to reach an agreement with the Spartans. The next day, during the Assembly, Alcibiades asked them what powers Sparta had granted them to negotiate and they replied, as agreed, that they had not come with full and independent powers. This was in direct contradiction to what they had said the day before, and Alcibiades seized on this opportunity to denounce their character, cast suspicion on their aims, and destroy their credibility. This ploy increased Alcibiades’ standing while embarrassing Nicias, and Alcibiades was subsequently appointed General.

Alcibiades’ first grand political stroke culminated in a formidable coalition of Peloponnesian city-states, led, of course, by Alcibiades, that rampaged through Sparta’s back yard and threatened both her territory and her esteem. Although that campaign ultimately was defeated at Mantinea, Alcibiades had cemented his reputation as a leader of boldness, valor, and cunning.

A Silver Tongue

Three years later in 415, Alcibiades set Athens spinning on a fateful course. Grandiose as ever, he used the request for military support from a Sicilian city-state to formulate a plan to expand Athens’ sphere of influence across the Adriatic. Nicias, who was vehemently against the proposal, unwittingly multiplied the size of the mission, and the Assembly placed him, along with Alcibiades, at its head. The new Sicilian expeditionary force would be larger than any contingent since the Persian Wars, and preparations for embarkation were begun in earnest.

As preparations were nearing completion, a religious scandal erupted in Athens. One night, a number of religious statues were defaced, and, though the perpetrators were never identified, Alcibiades and his followers were blamed. Alcibiades demanded that he stand trial before his departure, but the Assembly refused that demand, as they preferred to stage the trial after his return from Sicily. This was a calamitous decision, and Alcibiades knew it. After the fleet’s departure, Alcibiades’ enemies conspired to accuse him of more traitorous offenses, and Athens sent a ship to recall him for trials that were to begin immediately. Supposedly agreeing to return, Alcibiades escaped his arrestors, but to where? In the dichotomous world of late 5th century Greece, there was only one place to turn: Sparta.

Whether Sparta received Alcibiades out of fear of or respect for this charismatic figure or because they saw him as a traitorous defector alone, one cannot be sure, but receive him and listen to him they did. Alcibiades warned of the prowess of the Athenian expeditionary force and of the unbounded ambitions of Athens and promised that he would “render them aid and service greater than all the harm he had previously done them as an enemy.” 3 Convinced by his oratory, Alcibiades was elevated to military advisor and, through his advice, shifted the balance of Greek power to Sparta.

The tale of the apocalyptic fate of the expeditionary force is perhaps best told by my Professor of Greek history, Donald Kagan, and by Stephen Pressfield in his Tides of War, and I will leave the details, real and filled-in, to their highly recommended work. Suffice it to say that, under the overly-cautious leadership of Nicias and against the reinvigorated Spartans under the strategy of Alcibiades, the expedition was annihilated (literally), and the Athens’ economy, prestige, manpower, and morale were gutted. Furthermore, under Alcibiades, Sparta brought land war back to Athens, whose citizens had to retreat behind Athens’ fortifications, leaving their domestic sources of food to be ravaged. Just at the time Athens had to rely on its maritime superiority and Aegean alliances for sustenance, Alcibiades succeeded in tearing apart its confederacy, convincing a number of beleaguered allies that this was the time to revolt.

Buuuuut……

The Enemy of My Enemy

About this time, Alcibiades was piddling around where he shouldn’t’ve. The Spartan king’s wife and a baby, and, lo and behold, he looked a little bit too much like our controversial hero. Alcibiades had to flee again, but to where? He was a wanted man in Sparta and in his native democratic Athens where he had been tried and convicted in absentia for his supposed crimes.

Above, I used the term triangular to describe the Peloponnesian War, a conflict typically thought to have been fought between Athenian and Spartan confederacies. While Athens and Sparta were certainly the central players, a resurgent 4 and opportunistic Persia was interested in renewing its influence in the Mediterranean. It was to Persia that Alcibiades flew, still armed with oratory, charisma, and cunning, and increasingly with the status of military kingmaker–it was clear that he who had him had the advantage. In turn, in 412, Alcibiades transferred his allegiance to the Persians, much to the detriment of both Athens and Sparta. It was Alcibiades’ counsel to stategically cut funds to their beneficiaries (specifically, the Persians had been funding the Spartans to counteract the formidable Athenian confederacy in the Eastern Mediterranean) and to allow the Greeks to wear themselves out by mutual attrition. Only after they had weakened each other should Persia’s rebuilt fleet be fully put into service, to provide the coup de grâce to end Greek power. But was that end his true intention?

Meanwhile, Alcibiades was negotiating with Athenian power brokers. There was an age-old conflict in Athens between radical democracy and oligarchy, and Alcibiades approached potential oligarchs with a plan. If the powerful few interested in controlling Athens could succeed in changing the Athenian constitution to an oligarchy or narrower democracy, and if they could overturn Alcibiades’ conviction and have him recalled to Athens, then Alcibiades would affect the Persians to ally themselves with Athens. In the deal, Alcibiades claimed he would bring Persian money and a fleet equal to the size of the lost Sicilian force and transfer it to Athenian control. A whirlwind of ruse and counterruse involving an Athenian general who opposed Alcibiades’ proposals, a Spartan general, the Persian leaders, and Alcibiades ensued, and, in the end, Alcibiades’ proposals were rejected. He was not reinstated to Athens.

However, surprisingly, even without the promise of Persian support, the oligarchs (aided by Sparta) overthrew the Athenian democracy and replaced it with a small oligarchy. The coup of 411 did not go so well among the troops assembled at Athens’ second power base, the island of Samos. There, Athenian soldiers deposed the oligarchs and democratically elected their own leaders, the most important of whom was Thrasybulus. After a time, he persuaded the Athenian garrison to accept Alcibiades’ return, both in order to receive Persian aid which they thought may be forthcoming and so that Alcibiades might help them overthrow the “tyrants” now in control in Athens, itself. In his first speech to the assembled army, Alcibiades so inflamed their confidence that the army proposed to sail directly back to Athens to retake the city for democracy. Alcibiades calmed this initial excitement and suggested a course that did not amount to civil war. Meanwhile, due to instability, a narrow democracy giving assembling and voting rights to the middle class replaced the original oligarchy. 5 This government recalled Alcibiades into the service of Athens, proper. He then took the reigns fundraising and thereby won over the Athenian fleet’s rowers whose pay had been in question. In 410, Alcibiades was instrumental 6 in the Athenian naval victories at Abydos and Cyzicus which decimated the Spartan fleet and led the Spartans to sue for peace. In another fateful move, the Athenians rejected their advances. Alcibiades’ success continued, and he used his military acumen and persuasive skills to take the Thracian town of Selymbria without loss of life and to besiege and then take fortified Byzantium (now Istanbul). With Alcibiades in their pocket, Athens was resurgent and Sparta was reeling.

The Homecoming

Thus victorious, Alcibiades finally returned to his native city after eight dramatic years. Athenians packed the port to catch a glimpse of the famous man who returned with 100 talents of cash and numerous ships of war. Athens dropped all charges of sacrilege and treason and restored his property to him. In a propaganda coup, Alcibiades led a contingent of soldiers to clear and make safe the traditional terrestrial processional path of the Eleusian Mysteries, which until that year had to be celebrated at sea, as Spartans were until recently in control of Attica outside of Athens’ walls. It must have been a sweet homecoming. But all this glory came crashing back to earth. A combination of continued machinations of his enemies and naval defeat turned the tide. At Notium, while Alcibiades was with a separate detachment, a subordinate commander who was left in charge of his fleet disregarded Alcibiades’ explicit orders and brought about destruction of his fleet. Apparently unfairly blamed for the debacle, his enemies succeeded in removing him from command, and our discredited hero condemned himself to exile in Thrace, where he had made connections during the Selymbria campaign.

In a last attempt to save his countrymen and his own fate and reputation, he tried to intervene for Athens just before the calamitous battle of Aegospotami in 404. Perched in a Thracian castle above what was to be the field of battle, Alcibiades sent the Athenian commanders word of their strategic malposition. Refusing his intelligence, the Athenian generals and their fleet were obliterated by Spartan forces. With that final blow, the Athenian state gave way, and, after more than a generation of nearly continuous war, Sparta emerged victorious.

Alcibiades met his own violent end. The Spartans were now lords of Greece, and, still smarting from their wounds at his hands, sent assassins to track him down. Alcibiades had retreated to Asia Minor to try to enlist Persian help against Sparta, but was discovered by his hunters. Alcibiades’ house was set ablaze, and, with no hope of further escape, he armed himself with a dagger and rushed out upon his assailants who cut him down with a hail of arrows.

Such are the things charisma brings.

It’s a blessing and a scourge, and, for all its rarity, it’s an even rarer man who can wield it without falling victim to its associated temptations. So what do we make of Alcibiades? Was he good? Was he bad? Let’s not consider the world so black and white. We live in a time in which 2000 years of Christianity has shaped our ethics. But there was a time before Christian idealism saturated our world. Alcibiades’ time was even pre-ethics–when great thinkers were just formulating the concept. In the ancient, pre-Christian world (and beyond), the measure of a man was glory in life and fame after death.

If we use his time’s yardstick to measure him, he was a great man, indeed.

[divider]

1. Most of what we know of Alcibiades comes from Thucydides, Plato, and Plutarch (the former two were his contemporaries), but numerous other Classical sources, both contemporary (Xenophon, Isocrates, and Aristophanes) and later (Diodorus Siculus, Cornelius Nepos, etc.) help to paint his historical portrait. You can find all the ancient sources at the Perseus Project. In addition to the ancient authors, my main modern source is Donald Kagan’s The Peloponnesian War. Wikipedia also has a nicely written and well-referenced article on Alcibiades.

2. It should be noted that there was no distinction between common citizen and soldier in Classical Greece. There was no professional army; therefore, the citizens of each polis (city-state) picked up his own arms and fought alongside his neighbors and friends to defend or advance their polis’ causes.

4. Since their defeats at Salamis, Plataea, and Mycale.

5. Zeugitae: the class which could produce 200 bushels of goods per year. Also presumed to be the class who could afford their own bronze armor, the hoplite class.