Well, one of these cases are finally going to court. Unsurprisingly, in liberal California with its consumer-friendly laws.

It’s been years in the making. Law students have been trying across the country for years but have been batted away. The “law school scam” crowd has toiled away in their Mom’s basements, feverishly hoping that they will be vindicated. Now, after nearly a decade since graduating, and five years since she initially filed suit, a law school graduate is about have her day in court against her law school.

Anna Alaburda, graduated in the top tier of her class at Thomas Jefferson School of Law (“TJSL”) in San Diego in 2008. In doing so, she acquired nearly $150,000 in debt. Since graduation, she has yet to find a full-time salaried job as a lawyer. Alaburda initially filed suit against TJSL in 2011 as a class action.

Alaburda claims she was duped by TJSL’s employment statistics and wouldn’t have gone otherwise.

Did TJSL have inflated stats? Probably so.

But it’s also well known that TJSL is one of the lowest ranked law schools in the country. And Alaburda graduated into one of the worst law school/legal employment markets in history. For her to claim she didn’t know, she would have to have been willfully ignorant. Or as I saw one lawyer put it: “There is a reason she hired a Berkeley grad as her lawyer, and not a TJSL grad.”

Regardless, her claim breaks down as follows:

- Consumer is in the market for a service;

- Vendor offers that service;

- Vendor intentionally makes a representation of fact regarding that service;

- Vendor knows or should know that the representation is untrue;

- Vendor makes the representation for the purpose of inducing Consumer to purchase its service;

- Consumer relies on the untrue statement of fact in deciding to purchase Vendor’s service;

- Consumer suffers loss as a result of purchasing Vendor’s service.

Which is actually pretty straightforward. It’s not a ludicrous theory. Brian A. Procel, Alaburda’s lawyer, is going to argue that inflated statistics entices students to choose law schools that they might not otherwise – or at all. Six figures in non-dischargeable debt is a heavy burden.

Even as legal hiring dropped in 2011, according to Mr. Procel, Thomas Jefferson stated that 92.1 percent of its graduates were working at full-time jobs. That was a major increase from the 83 percent graduate employment the school claimed during the prosperous years of 2006 and 2007. But even in 2006, according to testimony expected at trial, a former school employee says she was pressured into inflating graduate employment data.

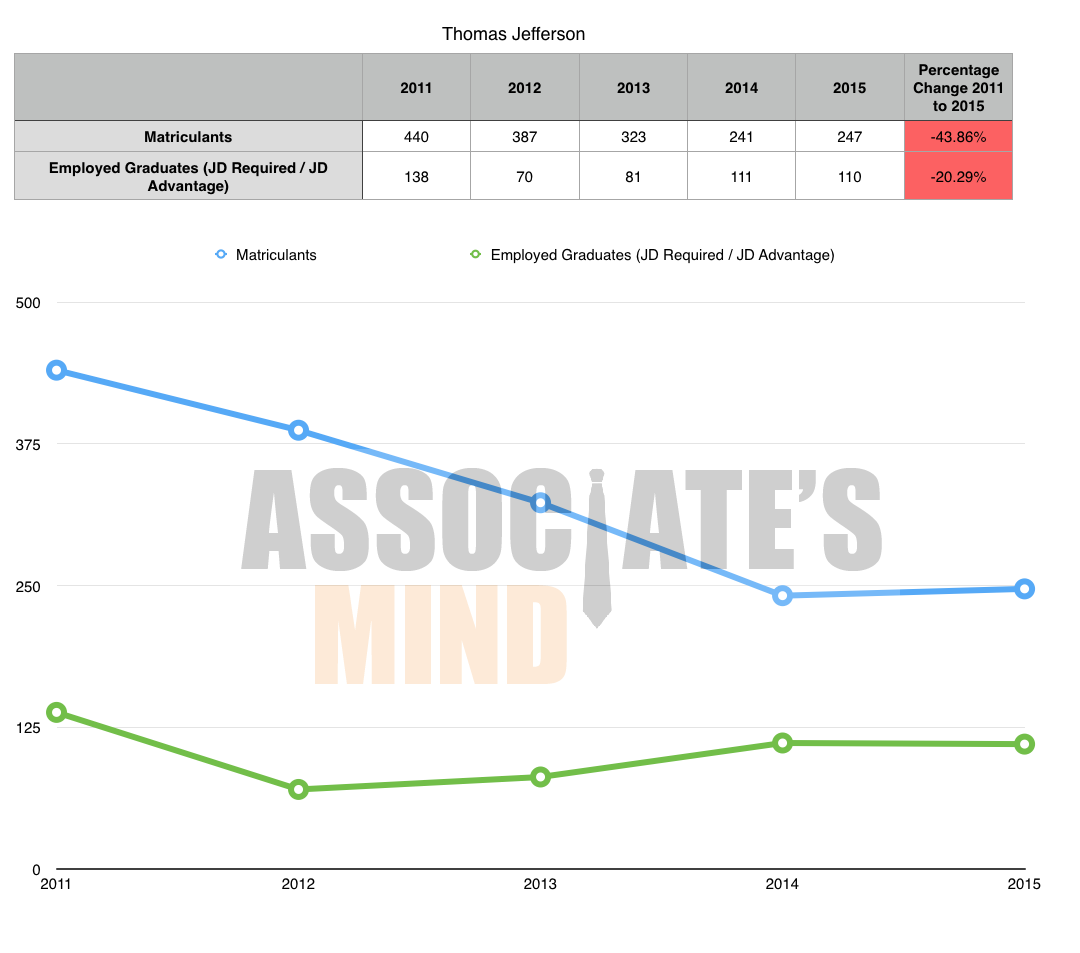

Let’s take a quick look at the publically available data on TJSL (fortunately, I keep records on all law schools at Associate’s Mind).

Now, this is from 2011 onwards, and Alaburda graduated back in 2008. But let’s look at matriculants v. employment statistics. Students matriculating in 2011, graduated in 2014. Those matriculating in 2012, graduated in 2015. That’s all we can examine at the moment.

Of the 440 matriculants in 2011, only 111 were employed in JD Required/JD Advantage jobs in 2014. That’s only 25%.

And of the 387 matriculants in 2012, only 110 were employed in JD Required/JD Advantage jobs in 2015. That’s only 28%.

If you pull the employment reports on TJSL, you’ll find that their total employment statistics improve some, but not by much. And I don’t think many people go to law school to get a job as a waiter. They go to law school because they plan on using their law degree to get a legal-oriented job.

So by that measurement, TJSL doesn’t look like it offers much to its students. But, Alaburda enrolled in 2005 and I’m sure the employment statistics were much rosier.

Caveat Emptor

Yet there’s no guarantee of employment in the legal field, or any field for that matter. You go to law school because it present you an opportunity. And Alaburda has an extra hurdle to clear with her lawsuit because she was presented such an opportunity – she was offered a job with a $60,000 salary shortly after she graduated – but rejected it.

The question now becomes: was she fraudulently induced? If so, what were her damages? Did she suffer damages from attending law school in general, or did she suffer damages from attending this law school specifically?

What about other living expenses? Housing? Books? Perhaps the opportunity cost of being in law school for three years? It’s a tough set of facts and nebulous damages.

Regardless, she is about to get her day in court.

___

P.S. – If you’re still in law school, instead of suing your school, you’re probably better off buying my book.